By Badou Edgar Khan

I came to this country with just ten dollars in my pocket, worked hard, and climbed up the socio-economic ladder to build a meaningful life for my family.

This familiar ‘rags to riches’ story may be a bit cliché—and mostly on point—but I know, as an immigrant, that the experience of thriving within a new country is usually more complex, especially for refugees and forced migrants.

My name is Badou Edgar Khan. I was born in Liberia, West Africa. When I immigrated to the United States from Liberia in the 1980s, I left my family with the hope of advancing my education. My father, who worked for the Organization of African Unity (OAU) mission to the United Nations, had a plan to send me to high school in New York. He provided me $3,500 to subsidize my education, housing, and food. And when my father returned home after helping me get settled, I was fortunate to have a strong support system in my home country that brought me solace.

Then, everything changed. What started as a small uprising in Liberia became a full-fledged civil war. By July 1990, Charles Taylor and his rebel forces breached the capital Monrovia, my home town. I lost track of my family and my world began to unravel.

I spent over a year searching for clues and hoping to find answers. Why did my family stay in the country so long to get caught in the crossfire?

Eventually, news arrived from my mother. She was in a refugee camp in Senegal, then Gambia and working to have my siblings flown from neighboring Cote D’Ivoire to be with her.

Meanwhile, I was in New York, sharing a room with friends and working jobs at a night club and a bus boy at a restaurant. I suddenly found out that my diplomatic immigration status had expired because my father had left the United States. Would that make me illegal?

I worked hard to afford to send money to my family, sometimes postponing payment on the rent for my room. I spent all of my money (which was very little) on legal fees fighting my own deportation. I finally received my permanent residency (Green Card) in November 1996. With more opportunities, I immediately took advantage of student loans and enrolled in college at NYU, while still bartending and working in clubs.

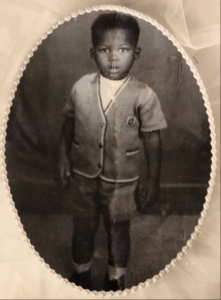

Left: Me at age 2 in Monrovia, Liberia. Right: Me at one of the many clubs where I worked in New York.

Eventually, I was reunited with my mother and siblings, who all made it to the United States. This process took several years with a lot of planning, as I was the only family member or relative who was able and willing to sign as their guardian for resettlement.

Today, as immigration policies in the U.S. hang in the balance, I reflect on my own immigration experience and the vulnerability of my family in Liberia. Over the years, I occasionally speak with my siblings and they reveal something new about their trauma of being forced from the only place they considered home. My sister has spoken about having to be constantly hidden from the gaze of young rebel fighters who were always attempting to take her as a wife during the five months they spent in rebel held territory. The times my brothers were being forcibly drafted as rebel fighters, to almost getting their necks slashed for protecting her against rape. The time my sister believed she would certainly die from drinking the same contaminated water that had killed other children. She thinks her saving grace was her father’s foresight to have them all immunized against cholera and typhoid fever just a few days before they had to escape. My grandmother died of cholera during the war.

In the years following our reunification, my family’s lives rollercoastered between good times and very stressful times. Eventually, I enrolled at NYU and graduated Cum Laude, almost a decade after I should have started college. My siblings all graduated college as well and settled into marriage and professional lives. But the scars of their past experiences are still present.

I believe forced immigration is one of the most destructive events in any person’s life. There is a perception that when people escape these events and are resettled, all is well. But forcibly displaced people frequently endure much hardship, including the psychological effects of trauma and the shattering of family ties across continents. As the immigration crisis continues to unfold today, I hope that we recognize and continue to uphold the critical importance of family reunification as a cornerstone of U.S. immigration policy. My family has lost so much, but we have each other. In the end, this matters to all of more than anything else.