By Julie Gersten

In August, I joined a delegation of Jewish leaders organized by HIAS who visited detention and migrant facilities on the U.S.-Mexico border. The experience afforded me access to the inner-workings of the U.S. immigration system: inside a detention facility where thousands of immigrants are kept in prison conditions; in court proceedings where complex and convoluted procedures shape the trajectory of those seeking refuge and asylum; behind the electronic fences where our government houses unaccompanied minors and separated children in legal limbo; and shelters in Tijuana where men, women and children fleeing for their lives await the opportunity to go North, or individuals freshly deported from the U.S. (some brusquely removed from their families and lives in the United States where they have spent decades) try to reunite with their children or just figure out what’s next for them.

Bearing witness is painful. It is impossible not to feel deeply impacted by the pain and trauma of the individuals inside the U.S. immigration system. Even more daunting is what bearing witness demands of me: the responsibility to share what I’ve seen, and the obligation to take action. I offer these observations and reflections from my experience as a first step.

Shelter for Unaccompanied Minors

The unaccompanied minor’s shelter, run by Southwest Keys, a private government provider.

Our first stop was a shelter for unaccompanied minors in the El Cajon neighborhood of San Diego. The shelter was located in a strip-mall setting, next to an auto-repair shop and behind a blanketed fence that prevents anyone from looking out or seeing in.

When children arrive at the border unaccompanied, they are transferred to the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement [ORR] under the Department of Health and Human Services. ORR is responsible for providing shelter, basic services and education to unaccompanied children while they await their court hearings and learn if they will be granted asylum or relief to stay in the United States. (ORR is also responsible for providing shelter to children forcibly separated from their parents at the border). While the facility was clean and met the basic needs of the children, it was far from adequate. In a small H shaped building, 65 boys between the ages of 6-17 eat, sleep and learn. When we were there, the children sat elbow to elbow in an overcrowded lunch room. The boys are entitled two short phone calls a week to a pre-approved list (in a public space where adults can monitor their phone call). Alarmed doors prevent them from leaving the facility, except for periodic fieldtrips. There is a small cement space in the back for outdoor recreation which felt hot and claustrophobic. It was hard to shake the feeling of captivity and the sense that the basic needs of a teenage boy experiencing trauma—privacy, freedom to roam—could not possibly be met in this shelter.

Most children who come unaccompanied to the U.S. arrive with the name and phone number of a family member or friend who has agreed to sponsor them. ORR’s role has been to house the children in shelters while they vet the sponsors to ensure that the children will be released to a safe environment. The average wait time in a shelter averaged about 30 days until children were released to the care of their sponsors. However, the Trump administration recently signed an MOU that requires all sponsors and all individuals living with sponsors to be fingerprinted, and their records transferred to the Department of Homeland Security. As a result, sponsors (especially those here without legal papers) are fearful to come forward, and many children have been left to languish in shelters for much longer periods of time.

Otay Mesa Detention Facility

Otay Mesa Detention Facility, run by CoreCivic, a private prison company that recently rebranded (formerly Corrections Corporation of America) after coming under intense scrutiny for poor treatment of inmates, bad oversight, inadequate staff, extensive lobbying and lack of proper cooperation with legal entities.

Next stop, Otay Mesa Detention facility, which houses 1,500 immigrants in a maximum-security prison setting as they await the outcome of their civil (not criminal)legal proceedings. We were not granted permission to tour the facility, but instead were allowed to observe court hearings in the immigration court inside the facility. Many people inside the detention facility are asylum-seekers—people who have fled persecution in their home country and have applied for protection but have not yet received any legal recognition or status. An asylum seeker, like a refugee, faces well-founded fears of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, and membership in a particular social group. Today, the majority of asylum-seekers who present themselves at the southern U.S. border are from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras. They are fleeing rampant violence and crushing poverty—literally running for their survival.

Asylum-seekers present themselves as the U.S. border and are then transferred to Immigration & Customs Enforcement [ICE] custody for a credible fear interview. If they pass the credible fear interview (meaning their claim of fear for their life is deemed credible), they are referred for a court date with an immigration judge. One example of how convoluted our immigration laws are: if you present yourself at the border and claim asylum using the proper channels, you are automatically detained with no option for parole. However, if you cross illegally into the country and are picked up by Customs and Border Patrol, you are eligible for parole. Essentially, if you cross illegally, you can await the outcome of your court proceedings while living freely in the United States. If you come legally, you are forced to wait out your court proceedings in a prison-like detention center. For many, that means years behind bars.

We learned that Otay Mesa detention facility is run like a maximum-security prison. Detainees are contained in cells with an open toilet and are often put into solitary confinement. Individuals with medical conditions, including mental illness, are often abruptly taken off their meds. Detainees wear prison jumpsuits, the color of which denotes their criminality. Blue jumpsuits = first border crossing. Orange = minor criminal history (i.e. crossing the border for the second time). Yellow = solitary confinement. Red = more significant criminal history. Detainees arrived at court in their jumpsuit (and sometimes handcuffed or shackled). So much for an unbiased court hearing. While detainees are entitled to a lawyer, they are responsible for securing legal counsel and paying. The vast majority of detainees represent themselves in court proceedings. Asylum and immigration laws are extremely complex, and without legal representation, individuals cannot possibly navigate the system successfully. It is not surprising to hear that legal representation is the most important factor in determining whether an individual will succeed in their case.

Instituto Madre Asunta, Tijuana, Mexico

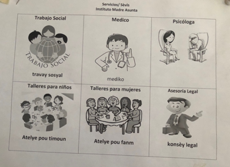

Left: The shelter has 44 beds, but serves 100-200 women and children each night. Right: A sign with the list of services that the shelter offers.

We began our second day by crossing the border into Tijuana and visiting the Instituto Madre Asunta, a shelter for women and children. Here, we saw women and children fleeing violence and extreme poverty wait for their opportunity to claim asylum at the U.S. Border. When the flow of asylum-seekers overwhelmed the streets of Tijuana, the Mexican government implemented a number system. Once you receive your number, you can go to a shelter and wait 3-4 weeks until you are called to present yourself at the U.S. border. The shelter is run by Madre (sister) Amelia Contini, who shared that she relies on prayer, meditation and the comradery of her sisters at the shelter to manage the emotional impact of working tirelessly to serve those in their greatest moment of need. All of the women and children who enter the shelter are fleeing trauma that is hard to imagine—kidnapping, murder of friends and family, extreme deprivation, rape. I asked the lawyer who prepares each woman for what to expect at the border if harsher immigration policies—prolonged detention, the possibility of family separation—has deterred anyone from claiming asylum in the U.S. She answered without hesitation, NO. These women are fleeing for their lives, and the possibility of detention or family separation is just another stumble in their journey to reach the hope and promise of the United States. That hit me hard—even in this dark moment, the U.S. still shines as a beacon of lights and hope for so many people who feel they have nowhere else to turn. Sadly, we learned that the light of hope quickly turns to despair as individuals arrive, are detained and navigate the brokenness of the U.S. immigration system.

While much of the energy and resources at the shelter are spent on housing and preparing women to apply for asylum, the shelter also supports women who are waiting to be reunited with their children. When a mother is deported from the United States and separated from her children, the U.S. government will not release them to her custody until she can meet onerous requirements—including gainful employment and a fully-furnished apartment with a functioning refrigerator. Madre Contini described these mothers as experiencing a near-death trauma. For many, the requirements are nearly impossible to reach.

Casa Immigrantes, Tijuana, Mexico

Casa Immigrantes has served over 260,000 migrants since 1987.

Our final stop was a men’s shelter down the block from the Instituto Madre Asunta. The shelter was built in 1987 to provide men with a place to sleep and rest before making the journey across the border. However, in recent years, they noticed a large increase in the number of men who arrived at the shelter immediately after being deported. The U.S. government deports people back to their country of citizenship, and many Mexicans are dropped at the border in Tijuana. They often arrive with no place to go and no plan for how to build a life for themselves. Many have spent decades in the United States where they have built homes, families and communities. As a result, Casa Immigrantes has changed its mission to focus on helping deportees find their way in Mexico. They offer job training and assistance, psychosocial support to get the men back on their feet and accustomed to their new reality (which includes the prospect of earning $10 per day instead of per hour), and—the most heartbreaking—classes on how to be a remote father.

Our trip came full circle when we arrived at the shelter and members of our group immediately recognized two men who had been defendants in an Operation Streamline court proceeding they observed the day before. Shackled, the men were tried together with 19 detainees in a criminal court proceeding that the group described as debased political theater. The men—who also recognized our group—agreed to speak to us about their experiences. Both men were immediately apprehended and detained when they crossed the border illegally on Monday, tried in an Operation Streamline hearing on Tuesday and deported to Tijuana on Wednesday morning (the day we arrived at the shelter). They looked bewildered and exhausted.

An image of Operation Streamline court proceedings, a “streamlined” criminal immigration proceeding with serious due process concerns. According to the ACLU, detainees “frequently have no counsel until their hearings, allowing little time to consult with an attorney to understand the charges and plea offers, consequences of conviction, and potential avenues for legal relief. Because a single attorney can represent dozens of defendants at a time, he or she might not be able to speak confidentially with each client or might have a conflict of interest among clients. Judges typically combine the initial appearance, arraignment, plea, and sentencing into a single hearing, sometimes taking as little as 25 seconds per defendant.”[1]

Pablo is 31 years old, from Veracruz and has four children. He lives in poverty and struggles to support his family. His wish was to find a job in the U.S., work to provide for his family and return to Mexico to reunite with them after a few years. He told our group, “In Mexico, everyone’s dream is the American dream.” Federico said he was 24 years old (though I suspect he was actually much younger), the son of farmers from Oaxaca and wanted a better life for himself. Both men relayed the trauma of their experiences. Pablo spoke through tears. Shackled, imprisoned in a facility with the lights on 24/7 so they didn’t know if it was day or night, they both chose to plead guilty and be deported rather than face another minute in detention. The lawyer who sat next to me (who had volunteered her time helping detainees apply for asylum in another detention facility) told me that detention conditions will break people in a matter of hours. At the end of the ordeal, Pablo was deported without any of his money or personal belongings.

As we crossed back into San Diego, I looked out the window at the wall that separates the United States from Mexico and the skyline of Tijuana in the distance. I felt deep compassion and sadness for the men, women and children I saw. It is hard to image the push and pull factors—the horrors and deprivations, the promise of hope, the pain and disappointments—that shape their journeys to the United States. I felt outrage towards a system that chews people up and spits them out with little concern for their humanity. Looking at the cement and barbed wire that divides us, I felt the absurdity of it all. Just there—right on the other side of that wall—are people we recognize as less than human; literally “alien.” The cement blocks us from seeing their pain, their hopes and ambitions as similar to our own. The Somali-British poet Warsan Shire wrote in the poem Home:

No one leaves home unless

home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as well.

Each person I encountered has a story. They have all endured arduous journeys to stake their claim to the American dream. Our country is seen as a beacon of light to the world, and it is not surprising that people in dire situations will do whatever it takes to get here. So, when we talk about comprehensive immigration reform, it can’t just be about who gets to stay and who has to go. Reform has to include due process, laws and procedures that humanize the individuals in the system—many of who have a credible claim for asylum and a legal right to be here. In the two days I spent at the border, amidst all the brokenness, I saw compassion: immigration lawyers fighting tireless for their clients; judges who looked detainees in the eyes and asked if they understood what was said; shelter operators who worked day and night to support people in their greatest moment of need; social workers who helped unaccompanied children navigate the system with heart and commitment. My hope is that we can extend this umbrella of compassion and create space in our laws and public debates for seeing those on the other side of the wall as just like us. Because they are.

[1]https://www.aclu.org/other/operation-streamline-issue-brief